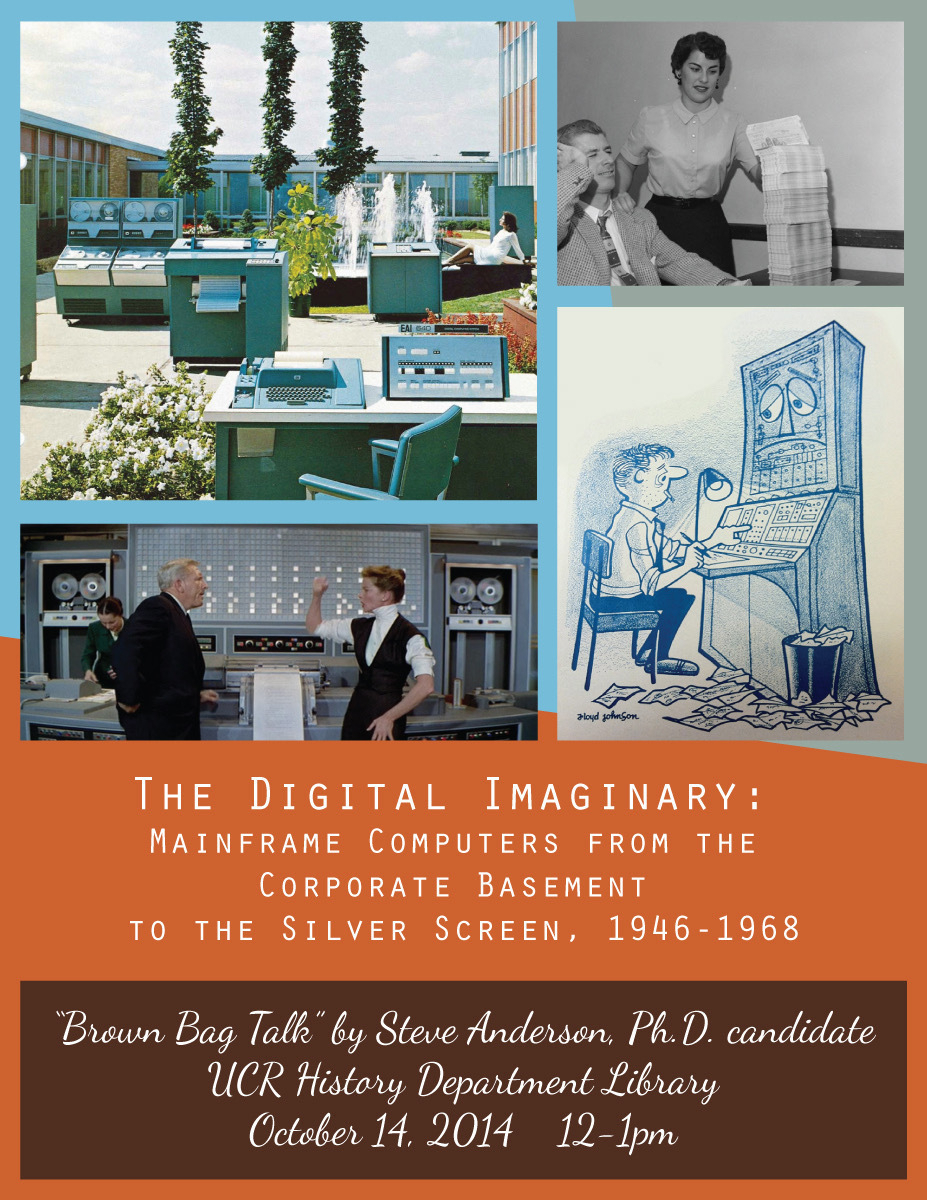

Hello, Goodbye - CDS Bids Farewell to Mainframe, Ushers in New Beginning

In 1998 the Catalog Distribution Service of the Library of Congress shutoff its mainframe computer and switched to a new system.

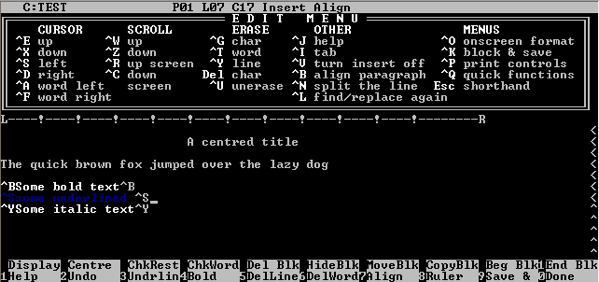

During the 1970s, the mainframes were used primarily to print catalog cards, which CDS once produced by the tens of millions. In those early days, as many as 30 staff members were required simply to service the units, performing such tasks as changing tape reels, threading tape and programming. "It was physically demanding labor," said Mr. Billingsley.

(Revised and republished April 2nd, 2025)