I created the infographic below for a Canvas certification course, “Humanizing Learning in Canvas.”

The course was part of the Canvas Certified Educator for Higher Education pathway.

I created the infographic below for a Canvas certification course, “Humanizing Learning in Canvas.”

The course was part of the Canvas Certified Educator for Higher Education pathway.

A new Apple Pro Display XDR is being rumored. I hope the price comes down, for the display and its accessories.

I remember watching the Apple WWDC Keynote in 2019, and there were some “boos” when the pricing for the display’s semi-optional Pro Stand was announced ($999 just for the stand). In my memory, I feel like the boos were louder during the live-streamed event than in the recorded version (the applause seems the same). John Ternus even pauses at the live audience’s reaction.

I have a Studio Display, which I love, but the camera quality and audio is a bit lacking. I use an Insta360 Link 2 instead of the built-in webcam.

A new Studio Display is also rumored, and hopefully the camera quality will be upgraded. A higher refresh rate would be a welcome addition too, especially for gaming.

What would also be nice, would be a lower-tier Apple display, designed for those with Mac minis and general computing needs. This would be like the 15-inch MacBook Air, filling a need (for quality displays – no more creaky plastic monitors), and also introducing more folks to Apple’s integration between software and hardware.

"Failure is a path, not an immediate result."(1)

I was listening to ATP podcast, and John Siracusa discussed “Coyote Time.”

The idea of Coyote Time comes from Wile E. Coyote cartoons, and it’s rooted in video game design.

In the Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner cartoons, Wile E. Coyote tends to end up just off the edge of a cliff, but he doesn’t fall until he realizes his dire situation.

At a glance, it would appear that Coyote Time is a moment of realization, a sinking feeling of impending doom. However, in video game design, Coyote Time is more about forgiveness and empathetic design choices. Coyote Time is about designing features into a game that provide a sense of reality apart from the harsh mechanics of the game itself.

Man and Computer: A Perspective, IBM, 1967 (Computer History Museum).

“In studying the principals, the first point is that a computer is quite dead. It can do nothing without someone to give instructions.” (4:05)

“But computers have no originality, no initiative.” (19:15)

“I’ve had it explained to me, but I still don’t understand it.” (The New Yorker, cartoon by Alan Dunn, 1957).

The “mop and pail” in the computer room were a constant theme for mainframes in the late 1950s and 1960s. In this cartoon the “it” is unclear, which is part of the humor. Is the “it” referencing computing in general, the fixation of people with computers, or an attempt to converse with the machine, or other possibilities?

The cartoon is from the book (with accompanying CDs of image files), The Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker, by Robert Mankoff and David Remnick, 2004.

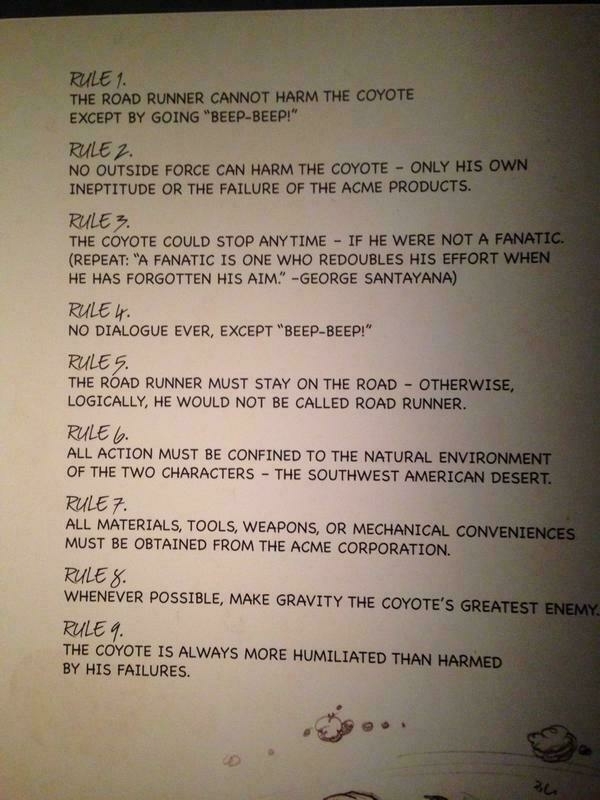

“No dialogue ever, except “Beep-Beep!”

I took this photo at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, New York, eleven years ago. This was just before being told by a docent that photography was not allowed in the exhibit space (sorry!). The exhibition was titled, “What’s Up, Doc? The Animation Art of Chuck Jones.”

Jason Kottke also posted “The Rules of Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote Cartoons” around the same time, in 2012 (a vintage post). The two versions are pretty close!

As Chuck Jones says in Chuck Amuck, “The rules and disciplines are properly difficult to identify. But there are – there must be – rules. Without them, comedy slops over the edges. Identity is lost.” (1)

This reminds me of Claude Shannon’s notion: “The rules of a game provide a sharply limited environment in which a machine may operate, with a clearly defined dial for its activities."(2)

When thinking of AI, it seems there are no rules at the moment. The game is being played while the rules are being made.

(1) Chuck Jones, Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of an Animated Cartoonist (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York: 1989), p. 224.

(2) C. E. Shannon, "Computers and Automata," in Proceedings of the IRE (Vol. 41, No. 10, Oct. 1953), p. 1237.

“First you must ask yourself…are you wealthy?”

The Laundromat on Netflix (2019) is quite good, and it’s an interesting way to make something like the Panama Papers more relatable. It seems that some films focus on the technology of the leak first (which I enjoy, of course), rather than how the physical world is impacted by the digital (which, as in The Laundromat, is more approachable and interesting).

Gary Oldman and Antonio Banderas are wonderful in the movie, they provide both comedy and information. In the educational technology field, this serving of “chocolate covered broccoli” is difficult – it’s either too much of one or the other. In The Laundromat, the satire is a perfect mix of alarming humor.

After watching The Laundromat we watched The Descendants, which is also a great film, and also deals with trusts, estates, and inheritance, among other things.

Maybe a rewatch of Knives Out or The Grand Budapest Hotel are next on the movie list.

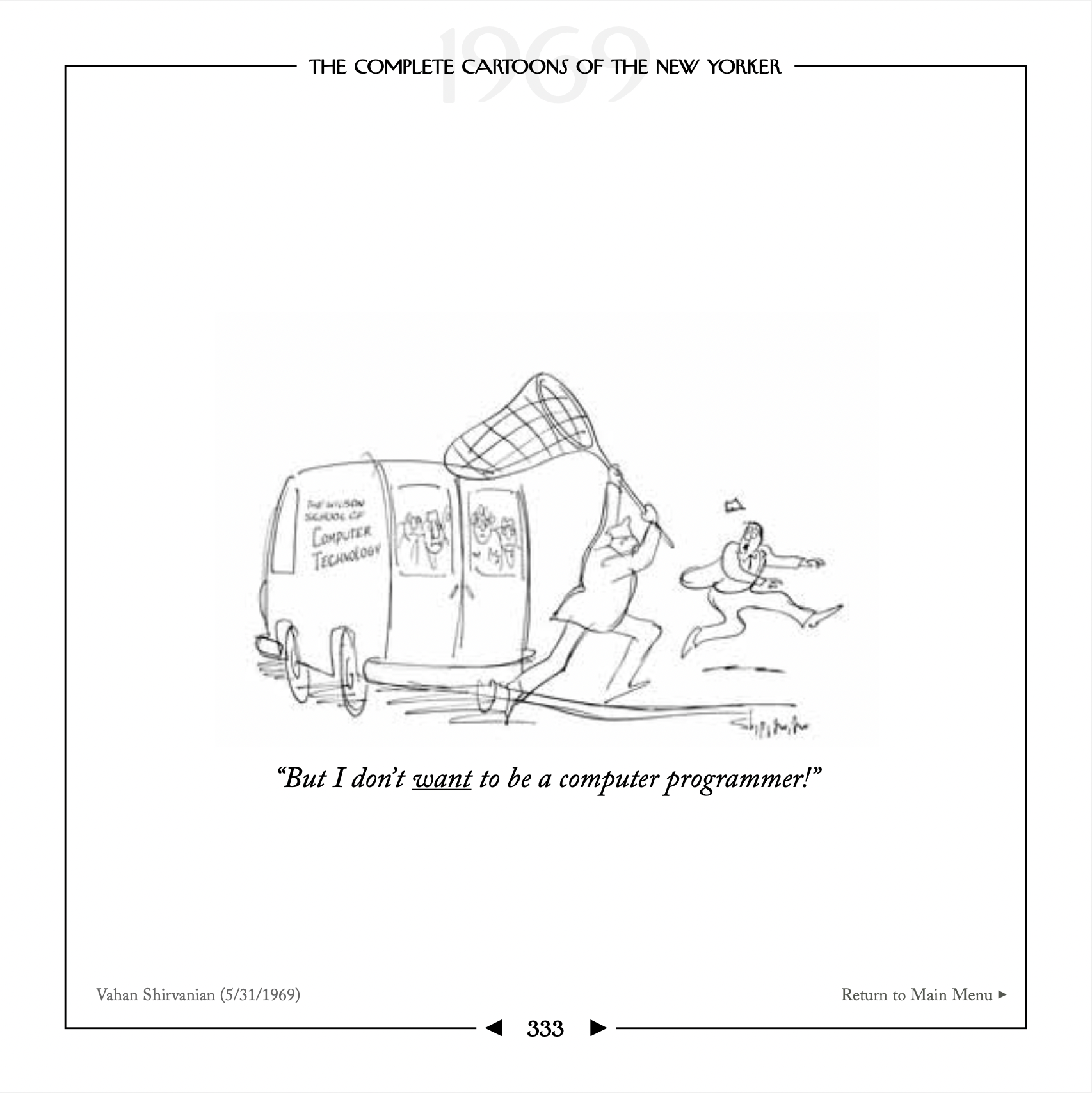

“But I don’t want to be a computer programmer!” (The New Yorker, cartoon by Vahan Shirvanian, 1969).

These days it’s more likely to be AI engineering than computer programming, but the rapid cultural change is similar.

The cartoon is from the book (with accompanying CD image files), The Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker, by Robert Mankoff and David Remnick, 2004.

John Oliver on Last Week Tonight regarding AI slop.

“AI slop is basically the newest iteration of spam.” (3:26)

“It’s not just that we can get fooled by fake stuff, it’s that the very existence of it then empowers bad actors to dismiss real videos and images as fake. It’s an idea called the liar’s dividend.” (24:33)

“AI slop can be…worryingly corrosive to the general concept of objective reality.” (25:46)

“The Professor and the Computer: 1985,” from Datamation magazine, August 1967 (pp. 56, 58).

This back-and-forth reminds me of the current state of Apple’s Siri, here in 2005…sorry, 2025.

Professor: Oh, put on the math. These monstrous time-sharing systems! I wish I had the good old 704 back again.

Computer: (After a short pause.) Sorry for the delay. I've located a 704, serial number 013, at the Radio Shack in Muncie, Indiana. Where and when do you want it delivered?

Professor: Oh, no! No. No, I don't want a 704.

Computer: But didn't you say ...

Professor: Never mind what I just said. I ...

Computer: Okay, I'll disregard your statement just previous. Now, where do you want your 704 delivered?

The notion that the computer would place an order for another computer, an IBM 704, also reminds me of Amazon’s AI-powered Alexa+ and its connection to consumers and online shopping.

The slow roll-outs of Alexa+ and Apple’s “new” Siri and Apple Intelligence are related to the complexity of LLMs and AI, especially in wide release to the general public. Tech companies are realizing that the “last mile is a lot farther away than they anticipated." It’s one thing to have an extra pack of kitchen sponges delivered, and another for a mainframe computer to show up on the doorstep.